World Economic Situation and Prospects: November 2024 Briefing, No. 186

Economic prospects and development challenges in landlocked developing countries

Economic prospects and development challenges in landlocked developing countries

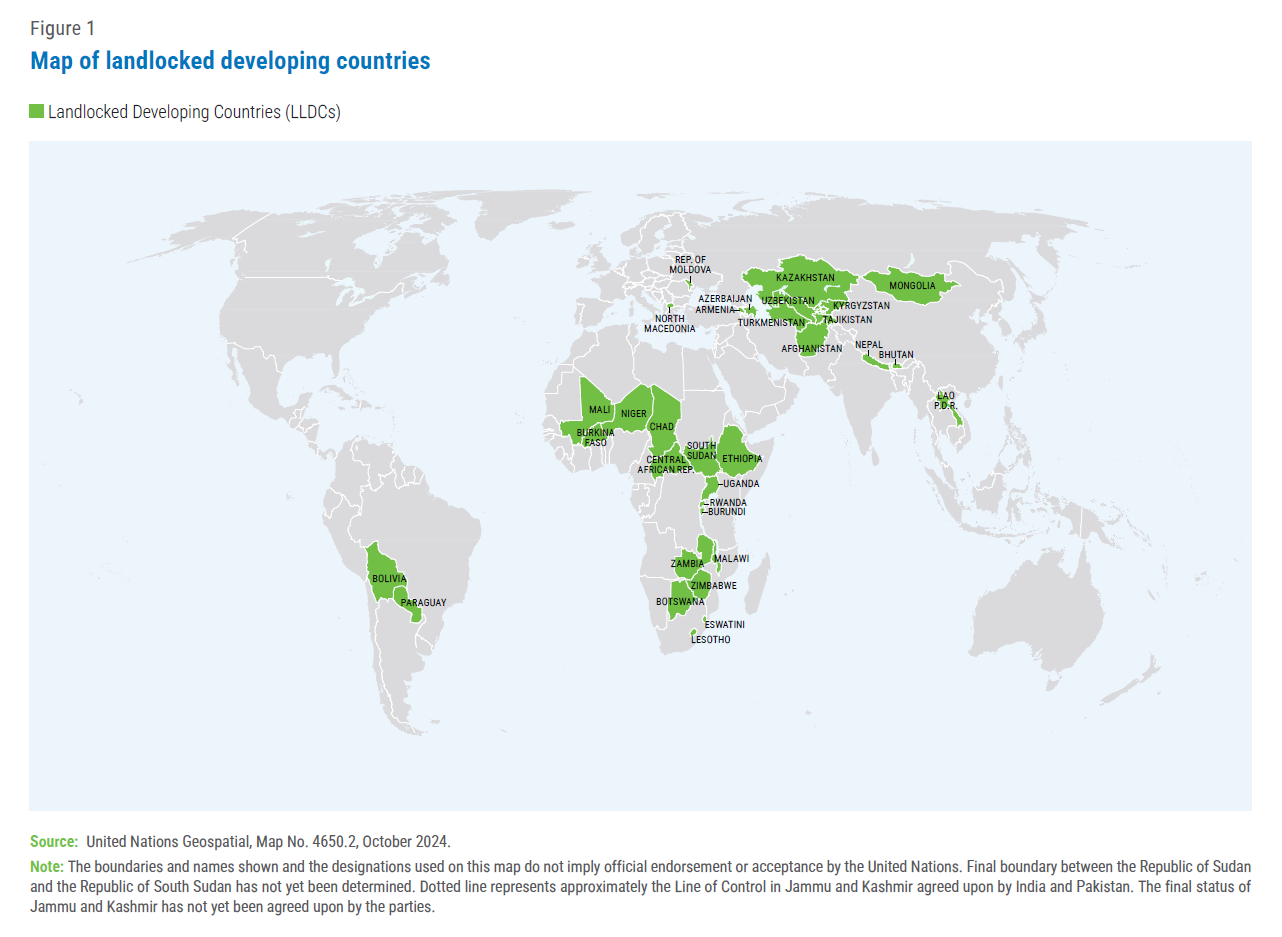

Multiple, overlapping crises in recent years have greatly undermined economic and development prospects in landlocked developing countries (LLDCs) (figure 1). Although growth of LLDCs has largely stabilized, the economies are still suffering from the scarring effects of the pandemic. Their structural challenges – ranging from geographic remoteness and reliance on commodities to lack of social safety nets and vulnerability to climate disasters – have exacerbated LLDCs’ fragility. The Third UN Conference on Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs), which will take place in Gaborone, Botswana on 10–13 December 2024, aims to address the challenges confronting the LLDCs and identify national, regional and international measures to unlock their potential. This Monthly Briefing will review the macroeconomic conditions in LLDCs in the post-pandemic era and discuss their development challenges, ahead of the conference.

Macroeconomic trends in LLDCs

After several years of mutually reinforcing shocks, growth rates in LLDCs have largely stabilized. In 2024 and 2025, growth of LLDCs is forecast at 4.7 per cent and 4.8 per cent, respectively, largely unchanged from 2023. However, the projected growth remains weaker than the pre-pandemic average of 5.3 per cent in 2010–2019. The current growth pace is not sufficient to recover the output loss due to the pandemic shock. During 2020–2023, LLDCs experienced an average annual output loss of over 6 per cent (compared with the pre-pandemic trend), greater than that of 4.7 per cent for developing economies in general. Least developed countries among the LLDCs are particularly vulnerable, with annual output losses continuing to widen and standing at over 10 per cent in 2023 (figure 2).

Within the group, the LLDCs in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region have continued to perform well. Wage growth and remittance inflows have boosted private consumption, while expansion in construction continues to support investment growth. Although conflicts in the region undermine growth prospects, the rerouting of trade has increased trade and transportation services in the CIS region. However, some countries face the risk of secondary sanctions stemming from transactions with the Russian Federation.

In contrast, African, Asian and Latin American LLDCs are expected to grow at a slower pace than before the pandemic (figure 3a). In Africa, in particular, droughts and floodings have ravaged output in many agriculture-dependent LLDCs, including Ethiopia, Malawi and Zambia. African LLDCs continue to grapple with financing challenges, high borrowing costs, and debt rollover risks. Political instability and conflicts affect exports or access to ports in several LLDCs, for example, in case of Ethiopia and Rwanda.

High commodity dependence makes LLDCs vulnerable to commodity price volatility. Lower prices of oil and some minerals – following a peak during the pandemic – have slowed growth in fuel or mineral-dependent LLDCs (figure 3b). The tepid global outlook and regional conflicts add uncertainties to the growth prospects of these commodity-dependent LLDCs.

Average inflation in LLDCs is projected to moderate from 14 per cent in 2023 to 10.5 per cent in 2024 and 7.3 per cent in 2025 but staying higher than inflation in developing countries as a whole (figure 4). Inflation in LLDCs, in general, has been higher than other developing economies due to their reliance on trade, high transport and trade costs, exchange rate volatility and sometimes governance challenges. The projected easing inflation in LLDCs reflects tighter monetary policy stances, lower global fuel and food prices, and easing global supply chain pressures. However, several LLDCs – especially in Africa – will continue to suffer the effects of elevated prices amid idiosyncratic challenges, such as political instability and conflict (South Sudan), elevated food prices caused by extreme weather events (Burundi and Malawi) and balance-of-payments challenges (Burundi and Ethiopia). Inflation of Latin American LLDCs is forecast to pick up, driven by Bolivia (Plurinational State of) due to food inflation amid severe wildfires and external imbalances.

Average inflation in LLDCs is projected to moderate from 14 per cent in 2023 to 10.5 per cent in 2024 and 7.3 per cent in 2025 but staying higher than inflation in developing countries as a whole (figure 4). Inflation in LLDCs, in general, has been higher than other developing economies due to their reliance on trade, high transport and trade costs, exchange rate volatility and sometimes governance challenges. The projected easing inflation in LLDCs reflects tighter monetary policy stances, lower global fuel and food prices, and easing global supply chain pressures. However, several LLDCs – especially in Africa – will continue to suffer the effects of elevated prices amid idiosyncratic challenges, such as political instability and conflict (South Sudan), elevated food prices caused by extreme weather events (Burundi and Malawi) and balance-of-payments challenges (Burundi and Ethiopia). Inflation of Latin American LLDCs is forecast to pick up, driven by Bolivia (Plurinational State of) due to food inflation amid severe wildfires and external imbalances.

Economic policy challenges amid recent crises

During the first nine months of 2024, a majority of LLDC central banks have reduced their policy rates amid easing inflation, with the exceptions of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malawi, and Zambia. Central banks in LLDCs faced difficult trade-offs in the past few years as they managed inflation and growth risks, balance-of-payments challenges, and currency weaknesses. Declining prices and demand for many commodities, rising trade restrictions, tightened global financial conditions, as well as losses in key sectors such as tourism over the past few years have adversely affected the balance-of-payments of many LLDCs. Concurrently, foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to LLDCs, which had been falling before the pandemic, remained subdued, exacerbating balance-of-payments pressures. In 2022 net FDI inflows to LLDCs totalled about $20 billion, below the 2015–2019 average of $22.1 billion and the all-time high of $35 billion in 2011.

Weak balance-of-payments positions also exerted downward pressures on LLDC currencies. Several LLDC currencies continued to depreciate in 2020–2023. Latest data in 2024 show that foreign exchange reserves in Armenia, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan stood just at or below three months of exports, threatening currency and financial stability (figure 5).

Fiscal conditions in LLDCs are equally challenging. Limited fiscal space constrained their capacity to roll out effective supportive measures during the pandemic. According to data from the IMF, on average LLDCs spent an additional 3.5 per cent of GDP in response to the pandemic and 1.9 per cent of GDP in liquidity support during January 2020 and September 2021, much below the world average of 10.2 per cent and 6.2 per cent respectively. The lack of sufficient fiscal support suggests the potential for significantly deeper and longer-lasting scarring of the LLDC economies. Increased public spending, declining export earnings and public revenues, and still weak GDP growth have further deteriorated fiscal conditions and heightened debt risks, which have forced many LLDCs to embark on fiscal consolidation even as large output gaps persisted.

Debt sustainability risks remain a major concern for many LLDCs. In 2022, external debt of LLDCs was on average 51 per cent of GDP, compared to around 15 per cent in developing economies. In 2022, the average total debt servicing costs on external debt are estimated at 22 per cent of export revenue of LLDCs, compared to 13.2 per cent for developing economies. Elevated interest rates in major developed economies and tightened global financial conditions in the past few years did not help the situation. As of end September 2024, five LLDCs are in external debt distress and six at high risk (IMF, 2024a). As of October, 13 LLDCs received funding from IMF lending facilities (IMF, 2024b).

Stalled progress to achieve sustainable development

Inherent structural vulnerability – including remoteness and limited access to international markets, long distances from the seaports, and high dependence on international trade – present unique development challenges. According to UN-OHRLLS, LLDCs on average pay more than twice what the transit countries would pay for transport costs, and take a longer time to send and receive goods from overseas markets. High transport costs and lack of infrastructure erode LLDCs’ competitiveness, discourage investment, limit economic growth. Against this backdrop, poverty incidents in LLDCs have remained high. In 2018, 26.4 per cent of LLDCs population lived below the international poverty line ($2.15 per day), only marginally improved from 28.3 per cent in 2014 and much higher than the world average of 8.8 per cent.

The COVID-19 pandemic and multiple shocks that followed have significantly set back LLDCs’ progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. High unemployment, a sizable informal sector and limited social safety nets have led to income losses and a rise in extreme poverty. Reduced household purchasing power in the face of rising prices of basic foods has heightened risks of food insecurity, which is further exacerbated by increasing climate related disasters in many LLDCs.

Unemployment rates in LLDCs have increased. In 2023, the average unemployment rate was above the pre-pandemic level and the world and developing countries’ averages, although the global rate fell to a record low since 2000 (figure 6). Gender gaps in unemployment rates widened from 2019 to 2023.

High unemployment rates are compounded by a large informal sector in LLDCs, leaving many workers without access to social safety nets, such as unemployment benefits, health insurance, or paid sick leave. In most LLDCs, more than half of the population is not covered by at least one social protection benefit; and in 11 LLDCs – nine in Africa and two in Asia – less than 20 per cent of the population has such coverage. As such, LLDC populations frequently lack any safety nets to weather large and unexpected shocks.

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising to observe weak growth in per capita income in LLDCs. As figure 7a shows, incomes of LLDCs have grown at a lower rate than those of the developing economies group during 2021 to 2023, after experiencing deeper contraction in 2020. Income growth of LLDCs in Africa, Asia and Latin America has not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels; that of African LLDCs, in particular, gradually slowed in 2021–2023 (figure 7b). Subdued income growth has translated to stalled progress in poverty alleviation in many LLDCs. By now, although global extreme poverty (below $2.15 per day) has returned to pre-pandemic levels, poverty reduction in low- and lower-middle-income countries – most LLDCs fall into these categories – have been less significant (Aguilar and others, 2024). For instance, the extreme poverty rate in Mali rose from 15.2 per cent in 2018 to 20.8 per cent in 2021; and in Zambia from 60.8 per cent in 2015 to 64.3 per cent in 2022.

Food insecurity has also worsened in LLDCs since 2020. Initially, pandemic-related border restrictions and lockdowns constrained the transport of food. Subsequently, increased world market prices resulting from conflict in Ukraine affected those LLDCs that depend on imported food grains and fertilizers. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the total population of LLDCs increased from 44.3 per cent during 2014–2016 to 51.9 per cent during 2021–2023, much higher than the world prevalence of 29 per cent in 2021–2023 (FAO, 2024). Food price inflation further worsened poverty, as poor households needed to spend a large part of their income on food.

LLDCs are extremely vulnerable to climate change. Since many LLDCs are highly reliant on natural resources and agricultural production, climate-related disasters – including droughts, desertification, biodiversity loss, melting glaciers, land degradation and disruption of transit links – impose high economic and social costs and further exacerbate food insecurity. Weak income growth, limited financial resources and the current challenging global environment hinder LLDCs’ ability to invest in mitigation and adaptation.

Limited productivity growth amid structural challenges

Structural challenges have been a key constraint to LLDCs’ economic development. Over the past decade, economic diversification largely stalled. Agricultural value-added in LLDCs only marginally declined during 2014–2022, staying higher than the world average, while manufacturing value added of has remained low since 2014 (figure 8a). At the same time, LLDCs’ export baskets largely contained primary commodities (figure 8b).

Limited economic diversification reflects subdued productivity gains. According to data from the International Labour Organization (ILO), labour productivity – measured by output per hour worked – increased only moderately from $7.9 in 2014 to $8.9 in 2023 on average, remaining at a level well below the global or the developing country averages.

To enhance productivity growth, LLDCs need good infrastructure, skilled human capital as well as strong institutional frameworks, a stable political environment and more favourable access to international markets. The Vienna Programme of Action (VPoA), a ten-year plan adopted by the United Nations in 2014, set these as priority areas to promote sustainable development of LLDCs, and its implementation will be reviewed comprehensively at the forthcoming Third UN Conference on LLDCs (United Nations, 2022).

International trade and integration into global value chains are crucial for boosting productivity through technology transfer, skills development and innovation. However, LLDCs’ participation in global trade remains relatively low. LLDCs’ exports have been less than 1 per cent of the world total in the past decades. In 2022, LLDCs’ annual exports per capita was approximately $410, only about 13 per cent of the world level. LLDCs’ lack of direct access to the sea and reliance on transit countries for external trade highlight the importance of trade facilitation. Yet, trade bottlenecks persisted during the pandemic and intensifying geopolitical tensions (WTO, 2021). There has been a threefold increase in the number of new trade restrictive measures across the world during 2019 and 2022 (United Nations, 2024), driven by protectionist trends and trade disputes.

Nearly one-fourth of the newly announced trade restrictive measures in 2023 alone affected LLDCs.

At the same time, transport costs have faced upward pressures. Data from UNCTAD show that shipping costs of imports to LLDCs increased by more than 40 per cent during 2019–2021. Rising and heightened fuel costs in 2021 and 2022 further strained container-shipping capacity and increased transport costs for LLDCs. Although many transport indictors have largely improved, prolonged and escalating conflicts – such as the war in Ukraine, restriction of trade through the Suez Canal, and tensions between Ethiopia and Somalia over port access since January 2024 – continue threatening to block or delay the movement of goods and to drive-up transport costs.

Transportation, electricity and communication infrastructure in LLDCs remains insufficient. Average road network length in LLDCs was about 80 meters per square kilometre land area in 2020, much lower than the developing countries’ average of about 300 metres per square kilometre. 40 per cent of LLDCs’ population still did not have access to electricity in 2022. The pandemic highlighted the importance of digital infrastructure, which is also critical for knowledge sharing and innovative e-government solutions, among others. Yet, nearly 60 per cent of individuals in LLDCs did not use the internet in 2023, lagging substantially behind other developing economies.

Lack of physical and digital infrastructure is linked to technology, knowledge and skill gaps. Many LLDCs have low levels of human capital development, with limited access to quality education and vocational training. On average, the mean years of schooling in LLDCs was about 7.7 years during the period 2014–2018, lower than the world average of 9.6 years. Skilled workers in LLDCs often emigrate to other countries in search of better opportunities, further limiting the human capital available within the countries. At the same time, LLDCs have constrained capacity in investing in innovation. In 2021, LLDCs research and development (R&D) expenditure only accounted for 0.2 per cent of GDP, whereas the world spent 2 per cent on average.

The way forward

The LLDCs’ distinct economic and development challenges underscore the need for focused attention on key areas including accelerating structural transformation and diversification, improving transport connectivity, facilitating cross-border and transit trade, strengthening digital connectivity, tackling climate change, as well as fostering trade and regional integration. Many of these will require sustained financial support, which many LLDCs are unable to finance given their high debt burdens and limited fiscal space.

LLDCs have taken policy measures to address these challenges over the past decade, such as mainstreaming the VPoA in national development plan (Bhutan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Nepal), promoting public-private partnerships for infrastructure development (Armenia), opening up the non-oil sector to foreign investment (Azerbaijan), upgrading ICT infrastructure (Nepal) (UN-OHRLLS, 2019). Various initiatives have been adopted to enhance regional partnerships in facilitating trade and connectivity and improving infrastructure, including the establishment of the Tripartite Free Trade Area and the African Continental Free Trade Area, the implementation of the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa, multiple bilateral and multilateral agreements on trade and transport infrastructure enhancement, and various economic corridors (UN-OHRLLS, 2024).

Going forward, LLDCs need to continue their policy efforts in sustaining economic recovery and securing social welfare gains. LLDCs’ embedded structural vulnerability, however, calls for stronger and more sustained support from the international community in the form of development aid, technical assistance, technology transfer, and regional cooperation and integration. The Third UN Conference on LLDCs, which will take place in Gaborone, Botswana on 10–13 December 2024, is expected to explore solutions and forge partnerships to address the challenges and unlock the potential of LLDCs for accelerating economic growth and sustainable development.

Follow Us